Interview Series

Obsessed with sound.

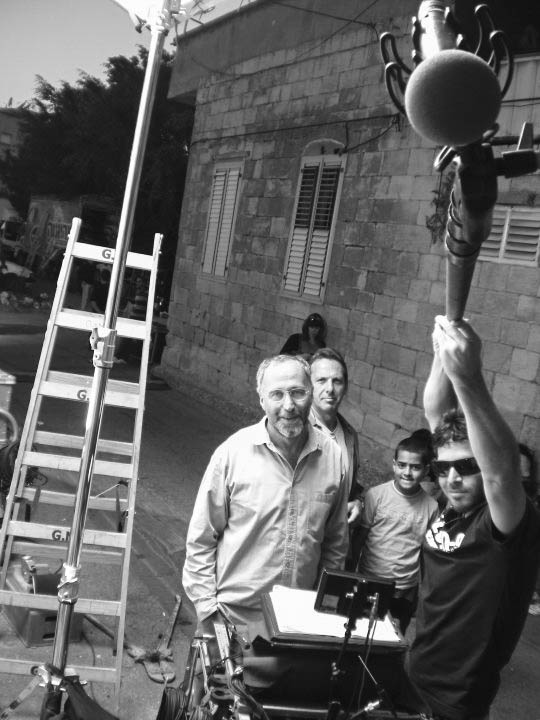

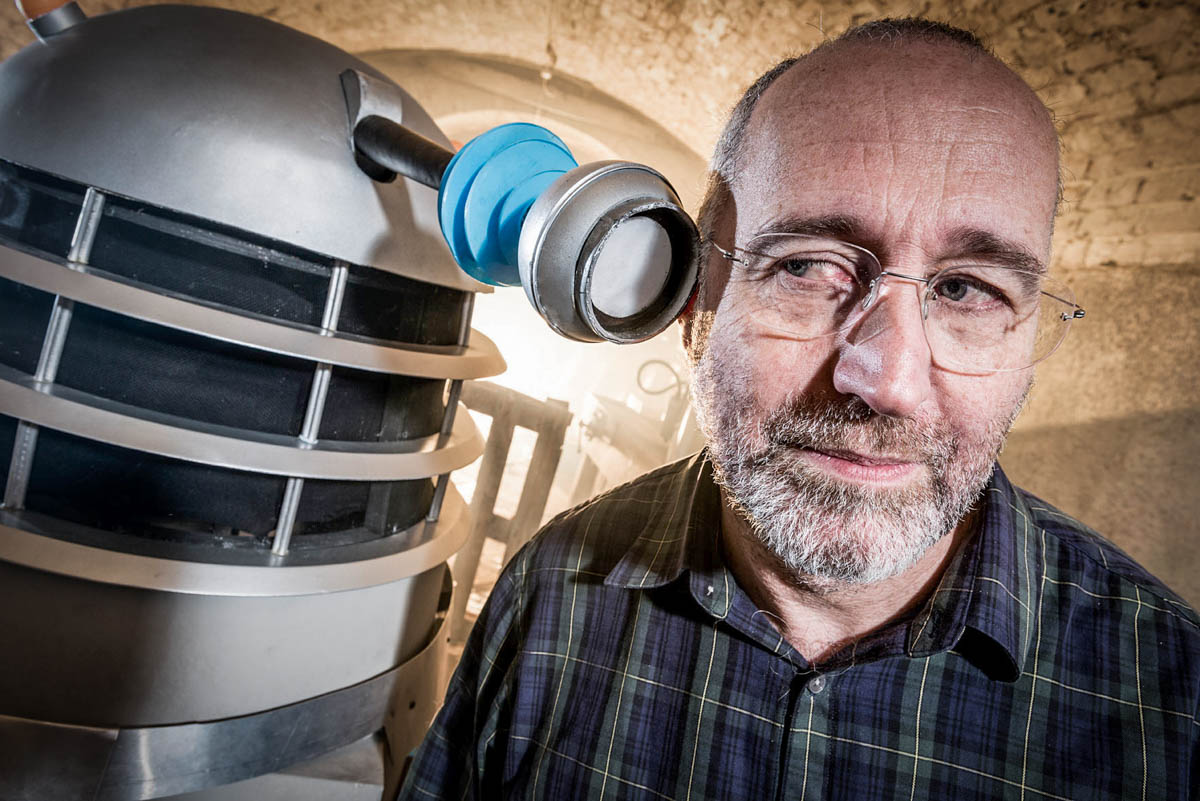

We’re delighted to speak with Simon Clark, Head of Production Sound at the National Film & Television School. Simon is a member of the Executive Committee of the Institute of Professional Sound (IPS) and a member of AMPS.

We’d like to take this opportunity to congratulate Simon and ‘Sound Team’, for the recent BAFTA win for ‘Wolf Hall’. As well as winning the Sound (Fiction) BAFTA, Wolf Hall also received RTS and RTS West of England nominations for best sound.

Tell us a little about yourself.

Where are you based, what do you do?

I’m based in North West London, and at the moment I’m both a production sound recordist and the Head of Production Sound at the National Film & Television School. This is a real departure for me, but it’s fantastic and I’m having the best of times.

I’ve been in professional audio since I was 17 years old. I absolutely love my job, and everything to do with sound. The fantastic thing about coming to a place like this and doing what I’m doing now is the huge enthusiasm that my students have for the world of production sound. They have to go through one hell of a selection process to get here, and those who get through have to invest an enormous amount of time, energy and money.

They’re full of enthusiasm, they’re full of this absolute will to learn, and they just want to know more about the industry. That’s enormously exciting for somebody like me, who’s still into all the traditions and the knowledge and all the things that I’ve got, but at the same time witnessing the cutting edge of what’s going on.

That sounds like an interesting dynamic. Given the ‘traditions’ of the industry and the way it’s always been done (and being a practitioner in an environment where young people might want to put their own stamp on things and innovate), is that an easy thing for you to facilitate, or do you find it a challenge?

I find it extraordinarily easy. It doesn’t mean to say that we always get it right when they (the students) question us, and when they decide they want to do something in a different way – but it is incredibly exciting. I think that it’s a sort of microcosm of what’s going on in the outside world really. There have been some landmark things that have happened – the biggest one obviously being the transition to digital.

I find it’s not a challenge at all; it’s just extraordinarily exciting, and it’s a very easy thing to get bound up in.

Just to go back a couple of years in that story then: how did you get into the Film & TV industry?

I think it’s probably quite a familiar story for people – certainly of my generation. There is a tiny bit of nepotism in there.

Basically, I was slung out of school, my academic career was quite catastrophic, and I wasn’t particularly interested in it… but I was obsessed with sound. I’d been obsessed from the age of about nine or ten, when my father – who was a film editor – brought a tape recorder home. In the 1960s, a reel-to-reel (small reel-to-reel recorder) was pretty much the same as having a CD player or an iPod: people just tended to have them. I was just absolutely enchanted by the physical aspects of this thing, then as soon as he made a recording and played it back to me, that was it: I was lost for the rest of my life.

It’s almost like an itch I have to scratch – to make recordings and play them back. Or, if somebody else has made a recording, I have to play it back and I have to know what’s on that medium. I can’t help myself. So, that was it: I was lost, I made a mess of school and left under a bit of a cloud. My father went to see a man in a dubbing theatre (where he had dubbed some of the films that he’d cut), and said to him, ‘Listen, the boy has left school. He’s driving his mother and I completely mad: all he wants to do is talk about sound and tape recorders, he’s spent all his money on tape recorders and microphones. Could you just take him on for a few weeks as a trainee, and knock it out of him? Make him sensible?’

So I went for 6 weeks, and then stayed for 7 years. I was in heaven! It’s the best thing that ever happened to me.

‘Basically, I was slung out of school, my academic career was quite catastrophic, and I wasn’t particularly interested in it…’

Simon Clark

Tell us a little more about the journey from those early post-production beginnings to the long and impressive list of British dramas on your resume. One thing I noticed looking at your resume/IMDB profile was that the title that you have for certain productions has evolved over time I just wondered whether you could give a brief insight into these different credits (i.e. ‘Sound Recordist’, ‘Sound Mixer’…)

Basically, I’m a ‘sound recordist’. You can call me what you want, but I am a sound recordist.

When I left the world of post-production and came out into the freelance world, I started off doing ‘corporates’ and little documentaries; things everybody starts off doing. Then I broke into the world of drama sometime in the late 1990s. Your job title may change, but it all means the same thing; it’s not like you’re doing anything different. AMPS – The Association of Motion Picture Sound – have a campaign to call Location Sound Recordists and Production Sound Recordists ‘Production Sound Mixers’; that’s what they want us to be called.

I’m completely happy with whatever it is, so there’ s no ‘journey’ there really; it’s purely what production decided to call me!

Looking at some of the productions that you have worked on – and thinking perhaps of the environmental conditions – what are some of the challenges for capturing great sound on location in Britain?

The great thing about the UK weather is that we all laugh and joke about it! It starts raining sometime in January and it finishes sometime at the end of December, and you know in that time that the wind will blow, the snow will fall and the hail will hail.

Gusty wind and rain are your main enemies. Most other stuff isn’t much of a problem. Snow is marvellous because snow deadens the world, and it gets rid of reverberations and background noise, because noise doesn’t travel so well in snow. But the wind and the rain are misery, really.

The wind…well, obviously you guys can do an enormous number of things about that, and it’s been getting better and better over the years. But there’s not much we can do about rain, really: it’s a killer. When it’s really, really raining and they insist on shooting, I think it’s a good idea to get the radio mics out and start relying on them more.

When we went back to the hotel that evening and played it back, I was just absolutely stunned: I didn’t even know we could do that, I’d never been in that situation before and I realised we could produce something that was absolutely fine in those conditions. All of the broadcast audio was usable.

You mentioned wind protection, and that is obviously something which Rycote supports. What’s your take on how that has evolved over time?

When I started, we always had the familiar ‘Zeppelin’ cage to go around the mics, and we also had the ‘Hi-Wind Sock’ (which seemed to be just a bit of slightly stretchy thick wool that went over the top of it). Then there was this massive leap forward when the Windjammer came out.

When that happened, I was just starting my documentary career, and I was travelling around the world recording in all sorts of places. At one point I was in New Zealand on a cliff top, and we were trying to do a piece to camera with a lady called Jancis Robinson on a thing called Jancis Robinson’s Wine Course, which was a fantastic gig. Three quarters of the year going around the world drinking wine from every wine-producing country on the planet – what’s not to like?

We decided we were going to do this piece to camera on a cliff-top in New Zealand and the topography there was just extraordinary; the wind was really blowing; it was just silly. It was very difficult just to hold the boom pole steady over her head as the wind gusted and I just thought, ‘This is utterly insane!’ The wind was rushing around my headphones as well, so I was hearing an enormous amount of wind noise and I didn’t know at the time how much of that was being recorded.

When we went back to the hotel that evening and played it back, I was just absolutely stunned: I didn’t even know we could do that, I’d never been in that situation before and I realised we could produce something that was absolutely fine in those conditions. All of the broadcast audio was usable.

What people have to remember is: the solution to any problem (whether it’s wind noise, handling noise, etc.) has to be something you can use when you are freezing cold, soaking wet, your fingers have gone numb and you are wearing thick gloves! It has to be user-friendly in extreme conditions, as well as doing its job. That’s why the evolution of the Rycote range has been so good: from the fiddly little elastics to the O-Rings and now to the Rycote Lyre system, that side of things has been fantastic.

What is in your kit bag? Is there even such a thing as a ‘standard’ kit bag? Do you swap and change things for different applications, or do you have a certain core of equipment that you always use?

It depends very much on the job you’re doing.

I’ve left documentary work behind me. It’s a younger man’s game, but obviously one used to have a ‘documentary kit’ and a ‘drama kit’, and while the two things overlapped they were most certainly not the same. Documentary kit has to be miniaturised; you’re going to have to have to carry it, physically carry it, all day long, sometimes while doing daft things like climbing up Angel Falls or white water rafting and parachuting – strange things we do when we are working on documentaries. It’s got to be lightweight and minimal.

With drama, we all get a little bit more ‘comfy’ with taking the kitchen sink and absolutely everything with us. My drama kit pretty much stays the same…except that it just expands as the years go by! More tracks, more microphones, and more ‘widgetty’ things that you discover that are quite useful to have with you. The van went from a short wheelbase to a long wheelbase quite a long time ago…

There is no wrong way and there is no right way. There’s ‘my way’ and there is ‘the guy next to you’s’ way.

What are some of the ‘staple’ items of kit you wouldn’t want to be without?

As far as I’m concerned – and it’s something I tell my students here at the School – there is no wrong way and there is no right way. There’s ‘my way’ and there is ‘the guy next to you’s’ way.

I’m a very ‘analogue’ boy! I love digital, and I think digital is wonderful and my recorder is obviously digital; but everything else I have at the moment is analogue. I use an analogue mixer and a Zaxcom Fusion as my recorder (a 12-track). That machine has the ability to process everything in the box: you can do all the EQ, the compression the delay, all in the box, in the machine itself; but I don’t do that. I don’t really use the machine to its full capability: basically, I treat it as a multi-track recorder and that’s all. The only buttons I press on it are ‘Stop’ and ‘Record’.

As far as I’m concerned, the Cooper CS 208 is the Rolls Royce of analogue location mixing desks. I used to use a Soundcraft, until one day a friend of mine came on the set of Waking the Dead to do some second unit for me, and had this beautiful looking mixer. I said, ‘What’s that? I haven’t seen one of those before?’ He said, ‘Oh it’s a Cooper: come here and push that fader up.’ The feel of the faders on the Cooper is second to none – it’s just extraordinary, and it cost me just over ten thousand quid within two weeks to have it. The Cooper is a workhorse, it’s pretty much indestructible, and I’ve had it now for ten years I think. The jury’s out what I buy next. Friends of mine encourage me to go digital, but I’m not convinced yet.

My mics are mostly Neumann. Neumann’s KM 100 Series mics are modular, so you can take them apart and you can put a piece of cable between the body of the microphone and the capsule, which means you can hide the capsule on the set or in a car or something and it becomes really, really small. I use a KMR 81 as a short rifle mic when I’m outside.

My boom poles are made by Panamic. I think they’re beautifully engineered, very long lasting and very easy to use. I use Audio Ltd 2040 radio mics. Until PTX plug-on transmitters came out, I didn’t think that radio booms were a good idea; I didn’t think the quality was good enough. But since the invention of PTX by Audio Ltd., I have used them. I’ve gone from being a person who never put a radio mic on the boom to being a person who almost never puts a cable on a boom nowadays.

The thing that excites me the most in terms of the way things are changing is digital for radio mics: we have to do it, because there is less and less and less frequency space available. And that’s just a fact of life: the government are squeezing it, and we need to be frequency agile. The only way that you can cram in more channels is to go digital; you can’t do it with analogue anymore so I’m really excited by the Audio Ltd 1010 range.

And what about the Rycote connection?

Now that the Cyclone has arrived (especially the smaller variant), I’m really excited by the idea of putting my KM 150s into a Cyclone mount and just clipping the cage over the top of it outdoors.

I can do that in about 7 seconds flat, and well: that’s fantastic! It means I don’t need two sets of KM 150s – one for interiors & one for exteriors – and all the accompanying storage problems. I can just have the pair of KM 150s that I use for interiors, and I can go outside and just clip the Cyclones on to have that flexibility.

I’m looking forward to that: it’s something I’m definitely going to be doing on my next gig.

‘If I were doing documentary now, I would definitely be using a Cyclone. After doing exterior stuff, you can walk indoors and dismantle Cyclone (which takes about 7 seconds)…’

Simon Clark

And the problem that the Cyclone is solving is the ability to quickly go from outside to inside with a basket system?

It solves quite a few issues.

The Cyclone solves the issue of having a wind cover that works when it’s got wet. The Windjammer is fabulous (as I mentioned previously with my New Zealand story), but when you are out in the rain all the fibres get matted and they are very difficult to dry out. The Cyclone solves that.

I did some tests for Resolution magazine for the Cyclone when it first came out and I was very lucky: on the day that I was doing the tests, it poured with rain! I set up a Windjammer on a microphone stand with a KMR 81 and a Cyclone on a microphone stand with a KMR 81 in it (both next to each other in my garden), and left them there for a day. The wind blew and we were doing lots of comparative tests, but the real killer was the fact that it absolutely lashed down with rain in the afternoon. A minute and a half later, and the Windjammer would just look like a dog that’s been for a walk or a bath, and the Cyclone didn’t look any different.

I took them indoors, and spent about a day drying the Windjammer. I gave the Cyclone a bit of a shake and popped it back on, and there it was: working again. That’s amazing, especially if you are in documentary world. And the speed of fitting it is another big plus as far as I’m concerned.

If I were doing documentary now, I would definitely be using a Cyclone. After doing exterior stuff, you can walk indoors and dismantle Cyclone (which takes about 7 seconds), drop the parts of the windshield in your bag, and continue without the windshield attached.

That’s feedback we’ve had quite widely. Somebody actually said to me last week (during an interview) that the best thing about the Cyclone is that it enables you to have no basket system on more occasions. Which was kind of shocking, given how much effort that goes into designing a material that’s going to have the most transparent sound. And for someone to hit you with something like, ‘the best thing about it is that you don’t have to use it…’

I reviewed the first one that came out. I’m married to an actor – she’s a stage actor but she also works in film & television. So I bring this thing home and she said, ‘What’s that?’ and I said, ‘This is the future, it’s fantastic, this thing called the Cyclone, look at that,’ and she said, ‘Geez, I’d hate you if you bought that on set and you hung it over my head,’ and I said ‘Why?’ and she said, ‘It’s enormous! And it’s black and I can’t keep my eyes off it.’

It’s in that review that I wrote for Resolution and sent to Simon, and I can tell you I’m single handily responsible for the fact they’re pale grey again!

Some other people have also said (regarding the colour), ‘Yeah actually this is much better.’

They’ve never been a problem before, because they’ve always been pale grey and you just kind of get used to them being there.

She (my wife) held the boompole up very briefly, and I just went, ‘Oh yeah, you are right: that is one hell of a thing up there, isn’t it?’ So it’s interesting, what you’re saying, about spending all that time with the wind reduction profile, the brilliance of the fabric and all that kind of stuff, and then somebody says, ‘I like it because I can take it off,’ and somebody else likes it because you made it grey again; because the bloody thing was too visible. Unintended consequences!

The director (with whom I work regularly) was Peter Kosminsky. The sheer scale of the production was a challenge: it’s a drama set in Tudor England, shot in 21st century England, 100% on location. And the cast was massive. We made a list of the number of people who had some form of dialogue (even just a scripted line), and there were 112 of them.

As a final question, what’s been the thing that stands out for you as being either something that’s provided the biggest challenge, or the most rewarding? Something you’d like to highlight from your catalogue of work.

If I got run over by a bus tomorrow, the job that I’m most proud of and enjoyed being on more than any other was Wolf Hall, without any shadow of a doubt; it stands head and shoulders above everything else I’ve ever done.

The director (with whom I work regularly) was Peter Kosminsky. The sheer scale of the production was a challenge: it’s a drama set in Tudor England, shot in 21st century England, 100% on location. And the cast was massive. We made a list of the number of people who had some form of dialogue (even just a scripted line), and there were 112 of them. Over an 18-19 week period, at some point or another we recorded the sound of 112 different people; even if one of them just said, ‘Yes, my Lord he’s in here,’ or whatever.

None of the noisy technology of the 21st century existed back then, of course, so to get clean useable tracks was a huge challenge. I used every trick and technique I know and worked in co-operation with the director and the location department. The more things we could capture successfully, the more it was possible for post-production to recreate the world of the 16th century. In the end the ADR line count for 6 hours of drama was less than 20 and some of those are new dialogue.

It was a brilliant, brilliant cast, and just the most interesting and fabulous script I’ve ever been involved in!