Interview Series

Documenting the Sounds of Nature.

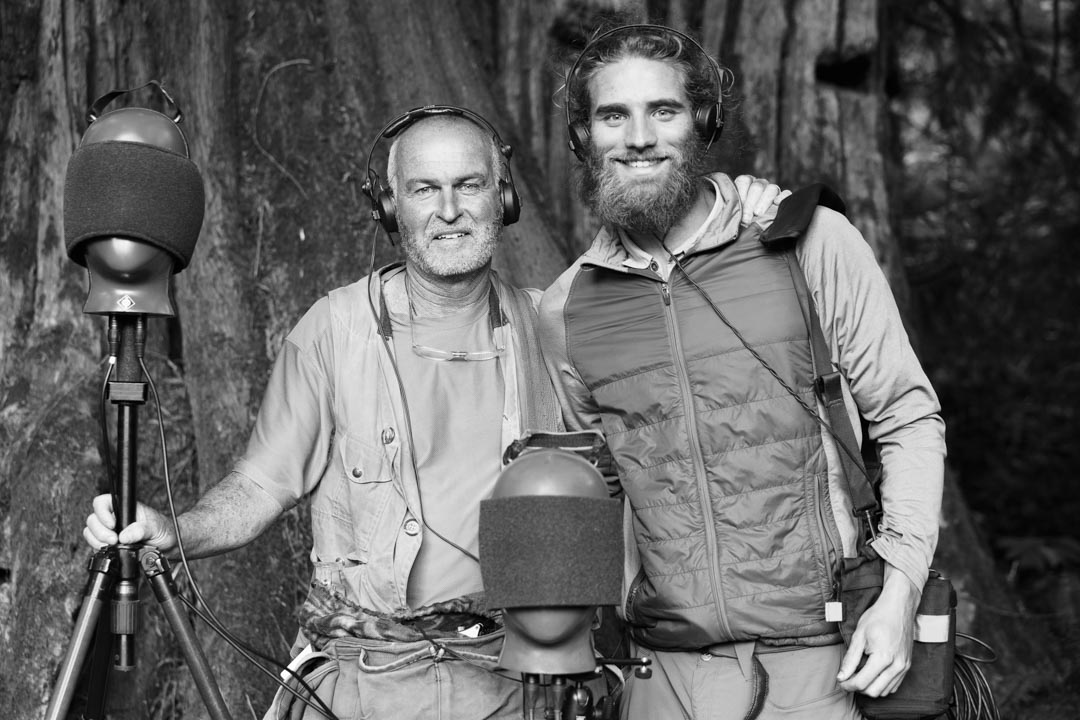

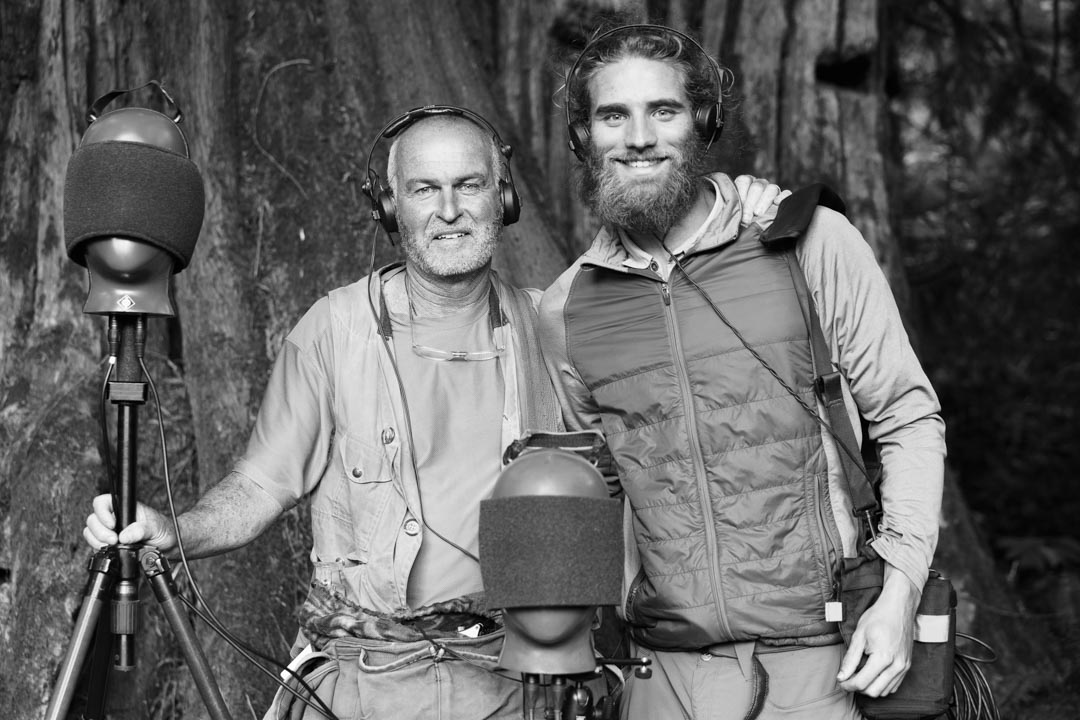

Palmer Morse and Matt Mikkelsen discuss the making of their much-lauded documentary ‘Being Hear’, which explores the work of Gordon Hempton — Emmy award winning nature sound recordist and acoustic ecologist.

Patrick Schaefer

Palmer Morse / Matt Mikkelsen

Web site:

Spruce Tone Films

Facebook:

facebook.com/beinghear

Instagram:

@sprucetonefilms

@palmermorse

@matthewmikkelsen

Tell us a bit about yourselves and your work.

P & M: A few years ago we met in Ithaca, New York. Still in college, it seemed that we both had this work ethic that really flowed well together. We both enjoy spending time outside and had no interest in trying to make our way or name in the machine of the narrative film industry. Eventually, we started working on short docs together, exploring subjects that not only interested us but felt as though they were important for the world to engage with. Palmer primarily focuses on camerawork while Matt focuses on audio.

We’ve definitely taught each other a lot in both of our specialities, and now we both direct, produce, shoot, record sound, and often edit together. At the moment Palmer lives in Oakland, California and works as the video producer at the Oakland Museum, while Matt lives in Ithaca, New York, and runs his production company Hayloft Audio LLC. Our goal, right now, is to create films that allow the viewer to learn something new or look at a subject they’re predisposed to in a different way.

It all started with disposable film cameras and the feeling of excitement when getting back the developed roll weeks or months later. It was and probably still is the closest thing to magic I’ve ever felt.

When did you realise you had a passion for what you do? Is it something that developed naturally, or was it something you suddenly decided to embark on?

M: I’ve always had a thing for photography, but I originally wanted to be a musician. Playing drums was my thing for many years, but I realized shortly after I started playing professionally that the hustle and grind of the music industry was forcing me to play music for other people, and not myself. I decided to go into the engineering side of music, learning to record, mix, and produce albums, which is what I went to school for.

Shortly after learning more about the industry, I decided that my love of nature was too great to spend all day every day locked inside a dark studio, so I set out to find a way to merge my love of sound recording with my love of the outdoors, and found Gordon. After some correspondence with Gordon, I decided to make the journey out to Washington State to study with him for a week, and learn how to record the sounds of nature. The first day of my personal “workshop”, we went out into the forest with a Neumann KU-81a binaural microphone at 4am, and within minutes of listening to the pristine soundscapes of the Olympic Peninsula, I was totally hooked. Since that workshop, I’ve spent the majority of my time listening to, recording, and analyzing natural spaces, and have become an advocate for protecting natural soundscapes.

Being Hear is a result of my efforts to spread the word about Gordon’s amazing work, and the importance of protecting our natural soundscapes. Sometimes things suddenly fall into place, and I think that’s what happened with Being Hear. I’ve only recently begun to call myself a documentary filmmaker, but it’s totally my dream job. I get to geek out about microphones and cameras, AND spend time outside… What could be better?

P: My interest in cameras definitely developed naturally for me. It all started with disposable film cameras and the feeling of excitement when getting back the developed roll weeks or months later. It was and probably still is the closest thing to magic I’ve ever felt. My mom had a digital camera for family trips when I was a kid, and I remember stumbling upon the video function and entertaining myself for hours.

Ultimately I channeled these interests by going to film school. When I was in there I had a difficult time sitting in classes that were solely about the art of filmmaking and the technologies related to such. I was taking classes outside of the school in sociology, anthropology, culture and communication, and when I had my first course in documentary it clicked. I would say making documentary film is my form of social engagement with the world, and I look for opportunities to work with people and places that are experiencing a serious environmental, social, or cultural issue that needs attention brought to it.

My hope is that through the moving image and sound, I can work with others to investigate and bring positive change.

‘The Rycote Softies also help prevent drops of water from entering the microphone capsules. They are an indispensable element to our audio kits, regardless of the size of our production.’

There has been nothing more rewarding than screening this film to an audience that is so intently listening — not just watching — that the air is almost electric.

CCan you tell us a little bit about your recent and much-lauded film about Gordon Hempton, Being Hear? Why did you decide to make it?

P & M: The real motivation for making Being Hear stems from our belief that Gordon’s work in the fields of sound-recording and acoustic ecology is incredibly interesting in its own right. It also encompasses so many other ideas that we find to be necessary for our society to think about right now. Being present and aware of our surroundings, gathering all the information available to us, making accommodations, and feeling a connection to each other and to nature are all things that we think are important.

Screening the film across the country and the world has been such an amazing experience we’ll be forever grateful for. The most incredible part of it has been the very fact that people are really getting and absorbing the complex ideas that Gordon and the film itself presents. There has been nothing more rewarding than screening this film to an audience that is so intently listening — not just watching — that the air is almost electric.

Making a film about sound was an incredibly difficult challenge.

Were there any specific challenges with the project?

P & M: Making a film about sound was an incredibly difficult challenge. It truly didn’t come together until we sat down in the editing room, and were able to make some creative decisions in the edit that allowed sound to come first and be the main focus of the piece.

The actual production was tricky when trying to exemplify the idea that the sounds of nature are beautiful, intricate, and important. Due to anthropogenic or human induced noise, it is becoming increasingly difficult to hear them in a natural setting without interruption.

Being given access to Gordon’s sound library was like opening a treasure chest. Imagine having access to pristine binaural recordings from every ecosystem on planet Earth.

With Gordon Hempton’s reputation as a nature sound recordist and unique approach to capturing sound, how did you decide to approach audio for the film? Did you have to make any changes or do things differently?

P: It’s a bit unconventional, but when we sat down to sort through our footage and set up a project in Premiere, we just started laying down clips in the timeline without any sound or storyboard at all. Eventually, we started looking at it like a puzzle, finding which clips fit visually after the next. We transcribed a long interview with Gordon, took our selects and plopped them under the visuals that made sense with what he was saying. The last thing Matt did that really married the entire film together was to take Gordon’s audio and his own recordings and basically sound design the film from scratch.

M: Being given access to Gordon’s sound library was like opening a treasure chest. Imagine having access to pristine binaural recordings from every ecosystem on planet Earth. It was hard to even maintain focus on the sound mixing and design, because I’d get so carried away listening to all these sounds I stumbled across. One thing I tried to do was to not amplify the sounds of nature too much in the mix, because that’s not how they exist naturally. I wanted people to have to lean forward in their seat to hear these incredible sounds, because it makes it more realistic. The other goal I had when mixing and editing was to only use sounds that were appropriate based on the ecosystem and time of year, which was a much more difficult task than I had originally thought.

The weather seems very changeable around Olympic National Park, where you filmed Being Hear. How do you deal with poor weather conditions when filming and recording sounds?

P & M: We were lucky in that the weather actually held out for us while we were there. Mornings were generally foggy and cool, but the sun would then rise and slowly burn it all off leaving nothing but blue skies and a few puffy clouds.

Despite this, the weather in Olympic National Park and the surrounding area is undoubtedly unpredictable, so we took some necessary precautions. We had several forms of rain protection for our gear bags, the camera itself, and audio equipment.

Gordon actually customizes a lot of his own gear, which is definitely pretty inspiring. Rycote products played a key role in our production, as nearly every microphone we use needs some form of suspension and wind protection. The Rycote Softies also help prevent drops of water from entering the microphone capsules. They are an indispensable element to our audio kits, regardless of the size of our production.

Do you have any exciting projects in the pipeline?u deal with poor weather conditions when filming and recording sounds?

P & M: Indeed we do! At the moment, we are working on a new film: again on the Olympic Peninsula. It’s quite disheartening to hear, but unfortunately a lot of the pristine quiet and wild featured in Being Hear is under threat.

We are currently working with the NPCA and Gordon to make a film about why this area needs to be protected from noise pollution. There’s obviously a lot more to this story that we won’t go into detail about now.